Maintaining healthy vision is essential for children’s growth, learning, and overall well-being. Yet pediatric eye health often does not receive the same level of attention as other childhood medical concerns.

By exploring the most up-to-date data, we gain a clearer picture of how common pediatric vision issues are, where disparities exist, and which interventions hold the greatest promise.

Over the past decade, researchers and health agencies have gathered expansive data on children’s eye health. This includes measuring prevalence across various conditions, such as myopia (nearsightedness), hyperopia (farsightedness), amblyopia (lazy eye), and more. It also tracks how many children receive routine screening and assesses the effectiveness of treatment programs.

By understanding these statistics, parents, educators, and policymakers can better target resources to ensure every child can see clearly and succeed academically and socially.

Key Statistics at a Glance

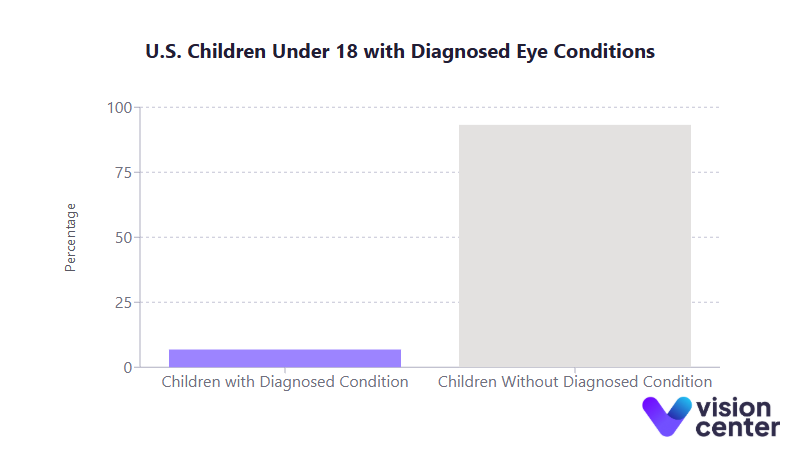

- An estimated 6.8% of U.S. children under 18 have a diagnosed eye or vision condition.

- About 1 in 122 children (over 600,000 total) experience uncorrectable visual acuity loss, with around 45,000 considered legally blind.

- In one recent survey, 25% of children aged 2 to 17 wore glasses or contact lenses, and this figure rose to over 40% among teenagers.

- Studies indicate that early correction of vision problems (especially amblyopia) yields a 70 to 80% success rate when started before age 7, significantly reducing permanent vision loss.

Understanding Prevalence and Trends

Understanding how many children are affected by vision problems is critical for shaping screening policies and providing adequate resources for treatment.

Common Pediatric Vision Conditions

Refractive errors, such as myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism, make up the bulk of childhood vision problems. In the United States, myopia affects roughly 4% of children under six years old and 9% of those aged 5 to 17.

Hyperopia exhibits nearly the opposite pattern, with about 21% of younger children having it, compared to around 13% of those in school-age years. Astigmatism, which blurs vision at multiple distances, appears in an estimated 15 to 28% of children 5 to 17.

Two additional conditions with significant impact are amblyopia (lazy eye) and strabismus (misalignment of the eyes). Both conditions often appear in roughly 2% to 4% of children. When unaddressed, these issues can lead to long-term visual impairment. However, early detection through screening can reverse or minimize the loss of visual function.

Geographic and Demographic Variations

Research reveals that the prevalence of childhood eye disorders is not uniform across regions. Several states with higher child poverty rates, such as Mississippi and West Virginia, have greater proportions of children with severe or uncorrectable vision loss.

States with large child populations, including California and Texas, naturally have higher absolute numbers of affected children, creating increased demand for specialists.

Demographically, Hispanic and Asian American children are projected to bear a growing proportion of pediatric vision impairment cases in the coming decades.

Meanwhile, socioeconomic factors, especially inadequate insurance coverage, continue to exacerbate disparities in early detection and timely treatment.

Myopia on the Rise

While amblyopia and certain types of pediatric blindness have shown modest declines through improved screening, myopia has been steadily rising worldwide.

Some international studies report extraordinarily high myopia rates among older children (up to 80 to 90% in certain populations).

Although U.S. numbers are lower, there is a clear upward trend associated with increased screen usage, reading at close distances, and limited outdoor time. This rising tide of myopia places added importance on comprehensive screening at younger ages.

The Role of Vision Screening

Vision screening programs are foundational to identifying at-risk children and facilitating early treatment that can prevent long-term damage.

Coverage and Uptake

Across the United States, the majority of children receive some form of vision screening by the time they reach elementary school. National data suggest that around 70% of all children ages 0 to 17 have had their vision tested, though these numbers vary with age.

In preschool-aged children (3 to 5 years), screening rates hover closer to 63% to 65%, rising as kids approach kindergarten entry. A key barrier is the lower likelihood of screening for children without insurance or in lower-income families.

In some states, fewer than half of uninsured preschoolers have undergone any vision test, underscoring significant inequities in preventive care.

School-Based vs. Clinical Screenings

Schools commonly conduct mass screenings for students at certain grade levels, especially where state law mandates these programs.

Approximately 40 states currently require vision screening for children in K–12, but fewer mandate screenings for preschool-age children. School-based testing often serves as the first detection point for many children, especially those who lack routine medical checkups.

Clinical screening in pediatricians’ offices or family practices is also key. Automation technologies (photoscreeners) have significantly improved the success of screenings for toddlers and preverbal children, tripling the rate of screening among insured children aged 1 to 3 over the last decade.

Still, the effectiveness of any screening program hinges on ensuring that children who fail receive confirmatory exams and follow-up, something that does not always happen promptly.

Disparities in Screening and Follow-Up

In states with robust screening laws or strong local partnerships between schools and eye care providers, more children are diagnosed with conditions like amblyopia at earlier ages.

In contrast, states with minimal requirements or inadequate funding often see many kids slip through the cracks. The COVID-19 pandemic further disrupted screenings in 2020–2021, potentially leaving millions of students untested or delayed in care.

Access to follow-up also remains a challenge, with some families waiting nearly a year or more for an eye exam after an abnormal school screening result.

Treatment Access and Efficacy

Once a vision disorder is detected, timely and effective treatment can make the difference between lifelong impairment and full recovery.

Corrective Lenses and Beyond

For refractive errors, the most immediate and straightforward intervention is providing the correct prescription for glasses or contact lenses.

Research consistently shows substantial improvements in reading, math scores, and overall academic performance for students after vision correction. These findings highlight the importance of simple solutions, like free or subsidized eyewear, for reducing barriers to care.

Amblyopia typically requires patching or penalizing the stronger eye to force the brain to use the weaker one. When started before age 7, this regimen succeeds in restoring normal or near-normal vision in the majority of cases.

Strabismus may be corrected with glasses (if the misalignment stems from refractive error) or through surgical interventions to realign the eyes. Beyond the functional benefits, successful strabismus correction can have a powerful psychosocial effect, reducing issues with self-esteem and social stigma.

Provider Shortages

Even if families have insurance or financial support, they may face significant geographic hurdles. Around 90% of U.S. counties lack a pediatric ophthalmologist, and several states have no in-state specialist for complex pediatric cases.

Pediatric optometrists, while more numerous, are also unevenly distributed. This “eye care desert” phenomenon can delay care and increase out-of-pocket travel costs for parents. Telehealth programs and mobile clinics are emerging strategies designed to bridge these gaps in underserved communities.

Insurance Coverage and Cost

Pediatric vision care is now considered an “essential health benefit” in many insurance plans, largely thanks to policy changes over the past decade. Medicaid covers pediatric eye exams, screenings, and necessary treatments through Early Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT).

While these expansions have boosted coverage rates, uninsured children are now only around 4 to 5% of the pediatric population, there are still challenges with provider acceptance of certain insurance plans and incomplete coverage of follow-up visits or replacement glasses. Despite increasing cost pressures in healthcare, untreated childhood vision disorders ultimately impose far greater economic burdens on special education services and lost productivity.

Vision and Child Development

Early identification and management of vision problems can dramatically influence a child’s academic, social, and developmental trajectory.

Academic Performance

Children rely heavily on vision for reading, writing, and engaging in classroom activities. Multiple studies link uncorrected refractive errors to lower test scores and reduced classroom engagement.

Conversely, students receiving prompt eyeglasses often demonstrate measurable gains in academic achievement and experience fewer classroom behavior concerns. Addressing mild yet persistent vision issues can prevent mislabeling children as having learning disabilities or attention disorders.

Long-Term Development

Treating amblyopia or strabismus in early childhood not only improves present-day functioning but also leads to better adult outcomes. A child who overcomes amblyopia is less vulnerable to total vision loss if the stronger eye is injured later in life.

Correcting strabismus can improve depth perception and self-confidence, potentially mitigating the social challenges these children sometimes face. Many research efforts have also examined the influence of family history, noting that children with myopic or amblyopic parents have a significantly elevated risk of needing vision care themselves.

Knowing this risk can drive earlier monitoring and possible preventive measures, such as increased outdoor activities for children prone to myopia.

Psychosocial Implications

Children with undiagnosed vision problems may avoid sports, appear withdrawn, or fail to meet developmental milestones. Strabismus, especially, can invite teasing from peers, leading to social anxiety or low self-esteem.

On the positive side, well-fitted glasses are often seen as stylish or “cool” by today’s youth, easing acceptance and encouraging compliance. The wider range of frame styles and lens options has also helped remove some of the stigma historically associated with wearing glasses.

Evolving Healthcare Delivery and Data Tracking

Ongoing improvements in how providers deliver care and how organizations track outcomes are key to reducing pediatric vision impairment at a population level.

New Approaches in Care Delivery

Telehealth is making modest inroads in pediatric eye care for specific tasks such as retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) screenings in neonatal ICUs. Some clinics use virtual appointments for follow-up visits or specialized vision therapy exercises.

Meanwhile, community-based and school-based programs with mobile eye units have reached hundreds of thousands of children who otherwise lack easy access to optometrists or ophthalmologists. These vans perform on-site comprehensive eye exams, with many delivering glasses directly to students.

Integrated Screening and Referral Systems

Many pediatricians now include standard vision checks during well-child visits, with electronic health records prompting them to perform age-appropriate screenings. If a child fails a screening, ideally there is a “warm handoff” to an eye care professional.

In communities with robust care coordination programs, often involving school nurses, social workers, or local health coalitions, families are more likely to follow through on referrals.

Tracking Outcomes

The past few years have seen better data integration through initiatives like the Vision and Eye Health Surveillance System, which compiles statistics from national surveys, claims databases, and other sources.

This more centralized platform helps researchers and public health officials evaluate trends in prevalence, assess the performance of screening mandates, and identify areas that remain underserved.

Similarly, large-scale studies continue to follow children over time to determine whether treatments like patching for amblyopia maintain their benefits as kids move into adolescence.

Final Summary

In recent years, pediatric eye health has received heightened attention from policymakers, healthcare providers, and community organizations alike. More children than ever are being screened for conditions that could impede their academic achievement and quality of life. Yet critical gaps remain.

Overall, the data clearly shows that timely identification and correction of vision problems can set children on a path toward brighter futures. Every effort to close screening gaps and facilitate prompt treatment can profoundly influence children’s developmental and academic trajectories.

A growing body of evidence confirms that maintaining good eye health is not only a medical necessity but also a cornerstone of educational equity. As more robust state and national surveillance systems come online, stakeholders can better coordinate care, focus on high-risk populations, and monitor progress over time.

The result is a more systematic approach to pediatric vision care, one that promises to reduce preventable visual impairment and empower millions of children to see the world with clarity and confidence.

In this article