Updated on June 12, 2025

Cataracts: Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis & Treatment

Vision Center is funded by our readers. We may earn commissions if you purchase something via one of our links.

Cataracts are common among older adults, often leading to progressive vision loss that can significantly impact daily life. You might find activities like reading, driving, or even recognizing faces increasingly difficult.

Fortunately, understanding cataracts and their treatment options can help you manage your vision effectively and confidently. Here's what you need to know about cataracts, from recognizing the early signs to exploring practical management strategies.

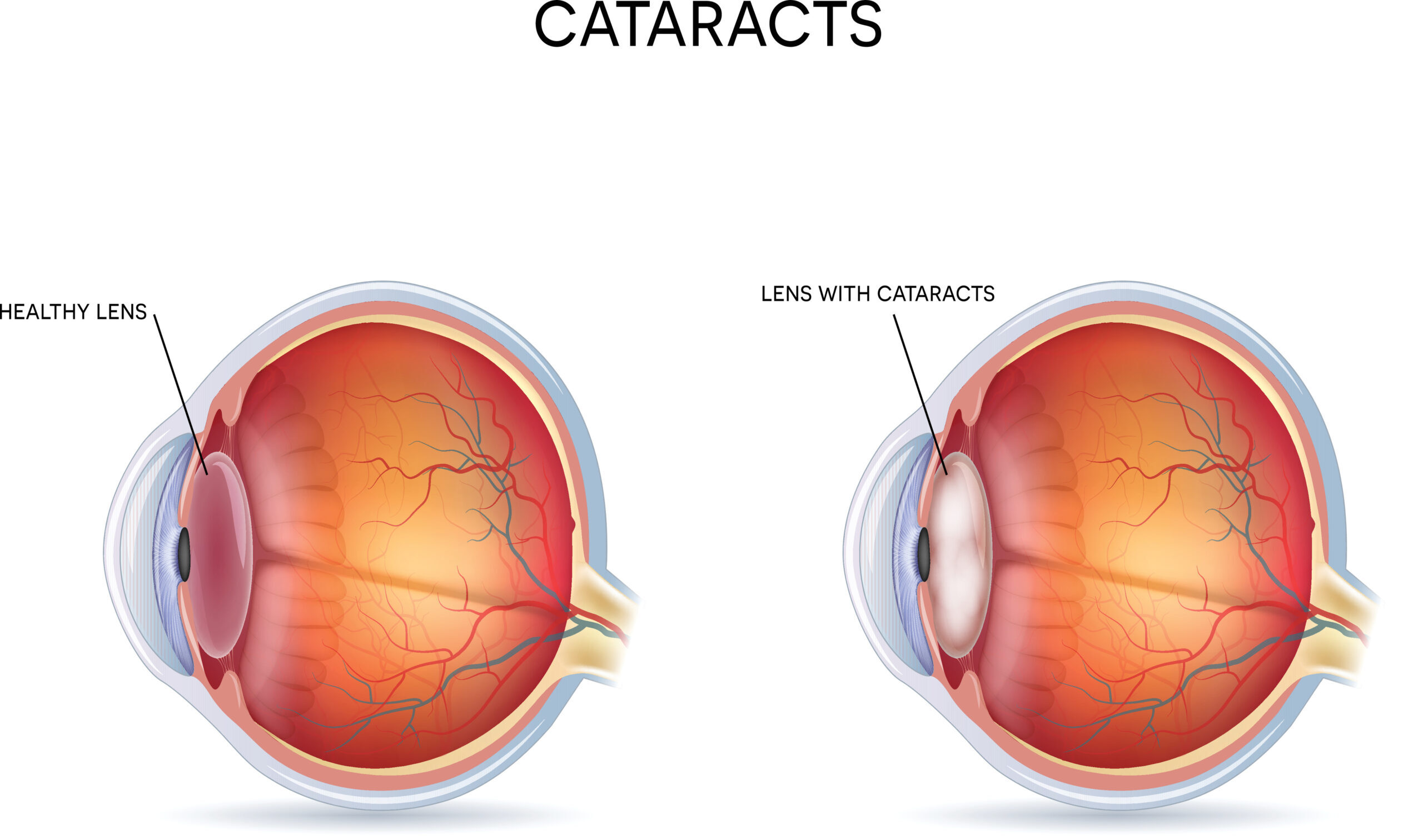

What are Cataracts?

Cataracts occur when the clear lens inside your eye becomes cloudy, often due to natural aging. More than half of all Americans aged 80 or older have experienced cataracts.

There are several types, each with unique features:

- Nuclear cataracts. They form at the center of the lens, typically causing gradual blurry vision and color fading. They're the most common type related to aging.

- Cortical cataracts. They develop on the edges of the lens, creating streaks or wedge-shaped opacities. They primarily cause glare and problems with night vision.

- Posterior subcapsular cataracts (PSC). They appear at the back of the lens, quickly causing significant glare and difficulty seeing clearly in bright light.

What Factors Affect Cataract Development?

Beyond age, certain factors can speed cataract formation:

- Ultraviolet (UV) exposure. Wearing sunglasses that block UV rays can help reduce your risk.

- Diabetes and smoking. Good blood sugar control and quitting smoking significantly lower your cataract risk.

- Medications. Long-term use of corticosteroids can increase the likelihood of developing cataracts.

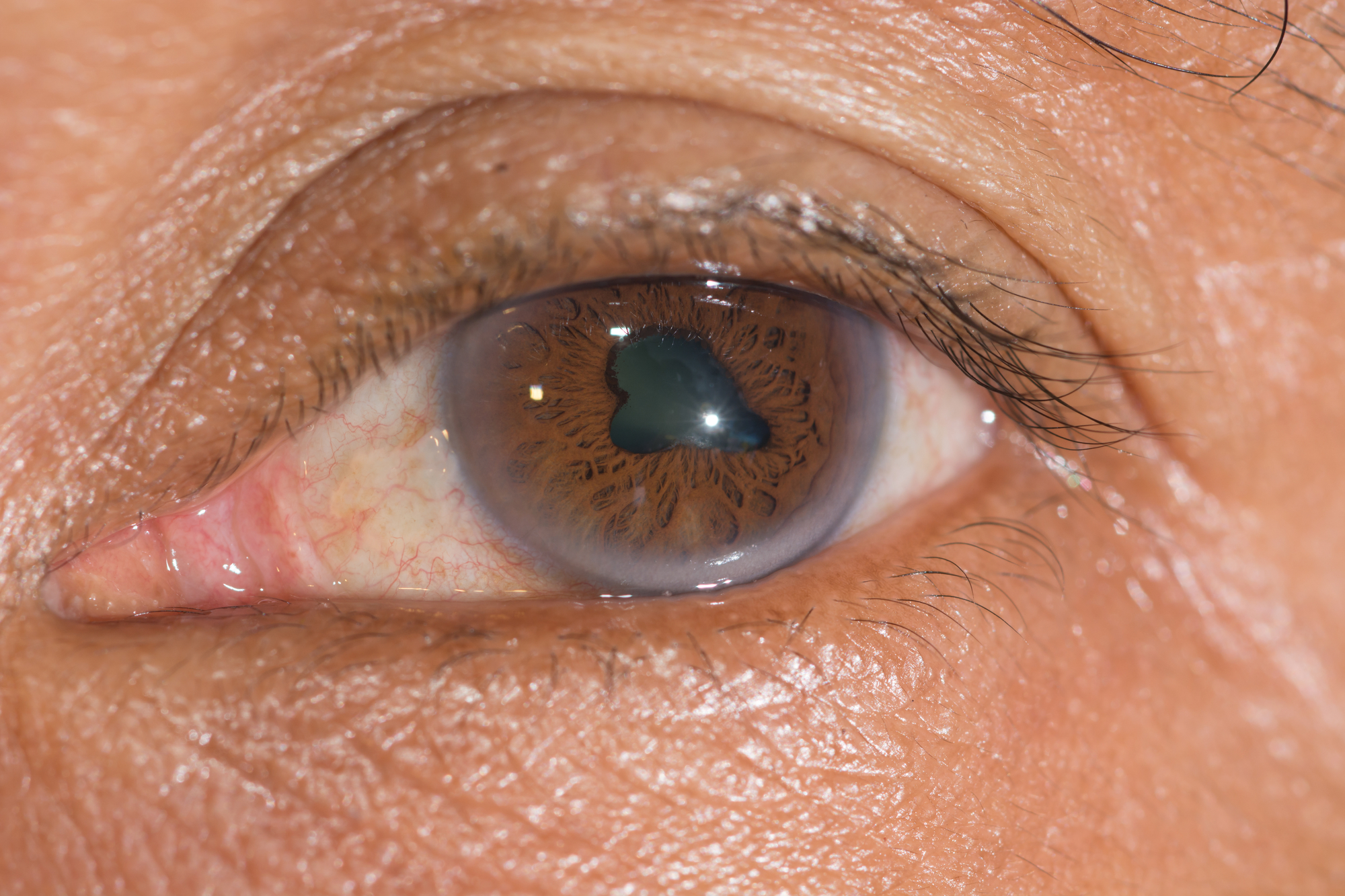

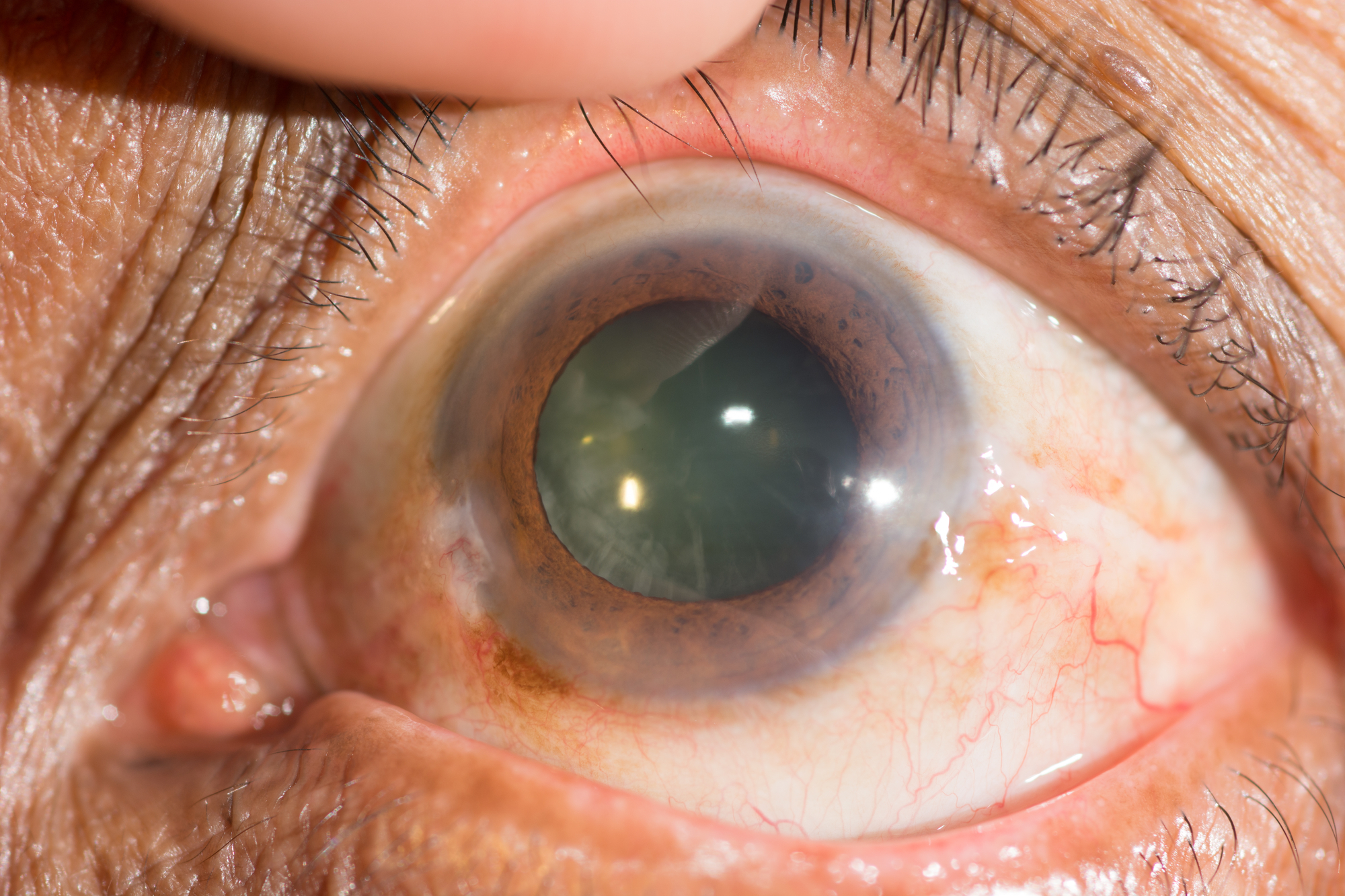

How to Spot Cataracts Early

Common cataract symptoms include gradual blurry vision, glare from lights, trouble seeing at night, and reduced color clarity.

Recognizing these symptoms early can help you manage your vision proactively. That’s why regular comprehensive eye exams are essential.

An ophthalmologist will typically perform several tests to evaluate your vision and eye health:

- Visual acuity test. Checks how clearly you see at different distances, often using an eye chart.

- Slit-lamp exam. A specialized microscope that allows the doctor to closely inspect your lens for cataracts.

- Dilated retinal exam. The doctor will dilate your pupils to thoroughly examine your lens, retina, and optic nerve health.

Additional tests may include glare sensitivity assessments, contrast sensitivity tests, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) to rule out other eye conditions.

How is Cataract Progress Tracked?

Doctors use standardized systems, like the Lens Opacities Classification System III (LOCS III), to objectively track your cataract progression.

Mild cataracts are typically monitored yearly, while moderate cataracts causing noticeable vision issues may require check-ups every six months.

If your vision drops significantly, usually around 20/40, or interferes with daily tasks, your ophthalmologist may recommend discussing surgical options.

How to Manage Early Cataracts

Even before cataract surgery becomes necessary, you can manage early-stage cataracts effectively through practical lifestyle adjustments:

- Update your eyeglass prescription. Cataracts often shift your prescription needs, sometimes improving near vision temporarily (known as "second sight"). Regular prescription updates can keep your vision clear.

- Increase and adjust lighting. Brighter task lighting and lamps with adjustable brightness settings can significantly improve reading and detailed tasks.

- Reduce glare. Wearing sunglasses outdoors, using window blinds, and choosing anti-reflective coatings on glasses can help minimize glare sensitivity.

- Use visual aids. Magnifiers, electronic readers, and large-print resources can assist if your cataract makes reading challenging.

- Evaluate supplements and eye drops carefully. Despite marketing claims, no nutritional supplement or eye drop has been conclusively shown to reverse or significantly slow cataract progression.

Taking these steps can significantly enhance your quality of life, helping you stay independent and active until surgery becomes a beneficial option.

What is Modern Cataract Surgery Like?

Modern cataract surgery has become one of the safest and most effective procedures performed today. It’s usually recommended when vision deteriorates to about 20/40 or worse, or significantly impacts daily activities.

Listen In Q&A Format

Cataracts Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis & Treatment

Vision Center Podcast

The primary method is phacoemulsification, a quick, minimally invasive procedure. This is what the process can look like:

- Micro-incision. The surgeon creates a tiny incision in the cornea.

- Lens removal. Ultrasound energy gently breaks up the cloudy lens, removing it through the small opening.

- Intraocular lens (IOL) implantation: A clear, artificial lens is inserted, restoring clarity and focusing power.

- Quick closure: The small incision typically self-seals without stitches.

Some surgeons offer a laser-assisted approach, called femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery (FLACS).

This option automates key steps and may reduce the ultrasound energy required, though studies show similar safety and vision outcomes compared to standard surgery.

Most cataract surgeries are extremely successful, with over 90% of patients experiencing significantly improved vision.

Recovery typically involves minimal downtime, with most people noticing clearer vision within days. They usually resume normal activities quickly, though strenuous activities should be avoided for about a week.

How to Choose the Right Lens Implant

Selecting the right lens implant (IOL) is crucial for achieving your best possible vision after cataract surgery. Several options are available, each with distinct advantages:

| Lens Type | Key Considerations |

| Monofocal | Provides sharp distance vision; reading glasses are typically required for close tasks. |

| Toric (Astigmatism-correcting) | Corrects astigmatism, improving clarity without glasses for patients with significant astigmatism. |

| Multifocal | Enables good near and distance vision, significantly reducing dependency on glasses, but may cause glare or halos around lights at night. |

| Extended Depth-of-Focus (EDOF) | Offers continuous vision from distance through intermediate ranges, with fewer halos than multifocals; some may still require glasses for very close tasks. |

| Accommodating | Designed to mimic natural lens focusing; provides good distance and intermediate vision, but near vision improvement is limited and can diminish over time. |

A popular strategy known as monovision sets one eye for distance and the other for near tasks, minimizing overall dependence on glasses. Ideal lens choice depends on your lifestyle, vision goals, tolerance for potential halos, and overall eye health.

How to Pay for Surgery

Financial considerations are important when planning cataract surgery. Here’s how typical coverage and costs break down:

- Medicare coverage. Medicare covers standard cataract surgery, including a monofocal IOL. After meeting your deductible, Medicare pays about 80% of the approved amount; you or supplemental insurance covers the remaining 20%.

- Premium lens and laser upgrades. Medicare does not cover advanced options like toric, multifocal, or laser-assisted surgery. Patients pay additional out-of-pocket fees, typically ranging from $1,000 to $3,000 per eye, depending on the lens or technology chosen.

Despite these costs, cataract surgery is considered highly cost-effective, significantly improving quality of life and reducing risks like falls and accidents.

When deciding, use this practical checklist:

- Clarify your vision needs. Assess how cataracts impact your daily life.

- Understand your lens options. Consider which type best matches your lifestyle and visual preferences.

- Review costs. Request a detailed estimate, including any premium upgrade fees.

- Discuss timing. Surgery should ideally occur when your vision loss affects your quality of life.

- Seek a second opinion. Ensuring you feel confident in your choices is critical.

Knowing exactly what to expect financially and medically helps you approach surgery comfortably and confidently.

Find an Eye Doctor

The best way to manage cataracts is to regularly consult with an experienced ophthalmologist. Schedule a comprehensive, dilated eye exam to discuss your specific vision needs and treatment options clearly.

In this article

7 sources cited

Updated on June 12, 2025

Updated on June 12, 2025

About Our Contributors

Lauren, with a bachelor's degree in biopsychology from The College of New Jersey and public health coursework from Princeton University, is an experienced medical writer passionate about eye health. Her writing is characterized by clarity and engagement, aiming to make complex medical topics accessible to all. When not writing, Lauren dedicates her time to running a small farm with her husband and their four dogs.

Dr. Melody Huang is an optometrist and freelance health writer with a passion for educating people about eye health. With her unique blend of clinical expertise and writing skills, Dr. Huang seeks to guide individuals towards healthier and happier lives. Her interests extend to Eastern medicine and integrative healthcare approaches. Outside of work, she enjoys exploring new skincare products, experimenting with food recipes, and spending time with her adopted cats.